Church Fathers & Medievals on the Biblical Canon

An EXTENSIVE list of 90+ Patristic & Medieval quotes undermining the Roman Catholic position on the Biblical canon

Introduction

If you’re a Protestant who has had conversations with your Roman Catholic friends about your differences, odds are that you have run into the fact that Roman Catholics (RCs) affirm a 73-book canon while Protestants generally affirm a 66-book canon. To be clear, Ecclesialists such as Roman Catholics, and Protestants such as Lutherans, Anglicans, and Presbyterians actually have identical New Testament canons. Where these traditions differ from one another is on the contents of the Old Testament canon.

Regarding the Old Testament canon, online RC pop-apologists love to sling about slogans like “Luther RIPPED books out of the Bible!” or “Protestants took books out of the Bible because those books disagree with Protestant doctrines!” and on and on and on the caricatures go.

The general talking point on the Roman Catholic side of the internet is that the Church down through the ages by and large (almost unanimously!) agreed with the Roman Catholic canon as later infallibly defined by the Roman Catholic church. As such, Protestants are charged with being innovators and heretics who, in an unprecedented manner, unjustly ripped books out of a Biblical canon that was authoritatively and universally settled eons before.

The Official Roman Catholic Canon

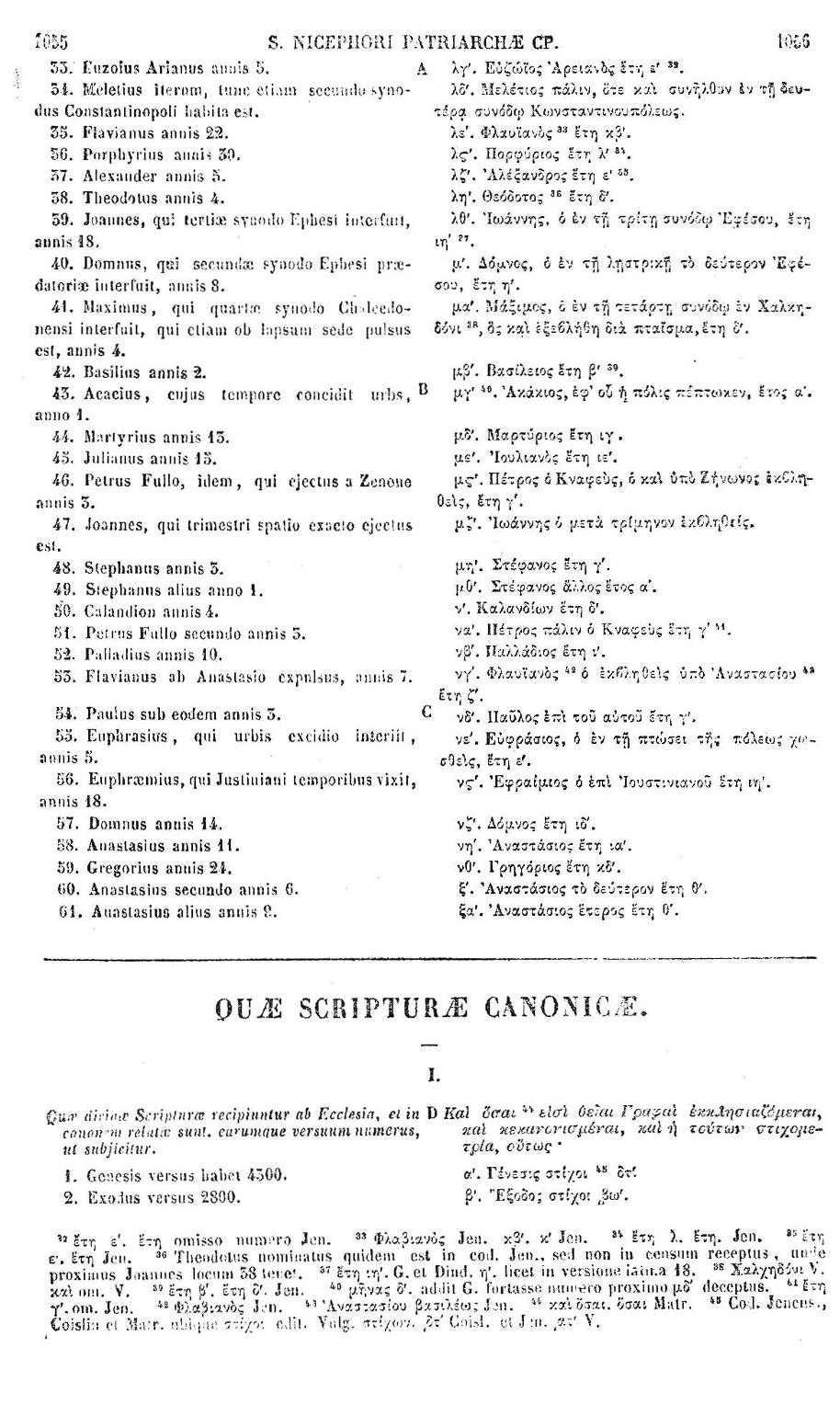

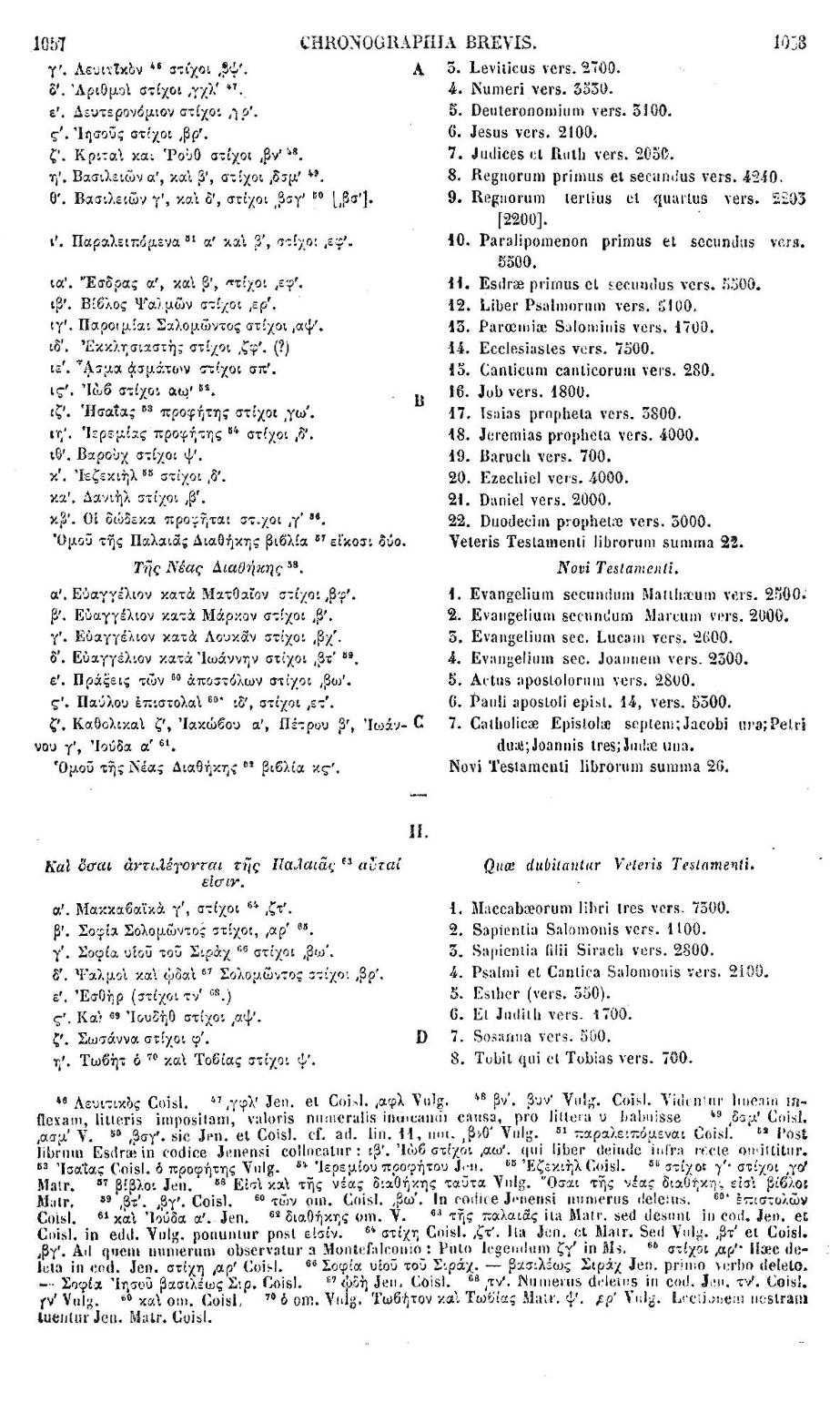

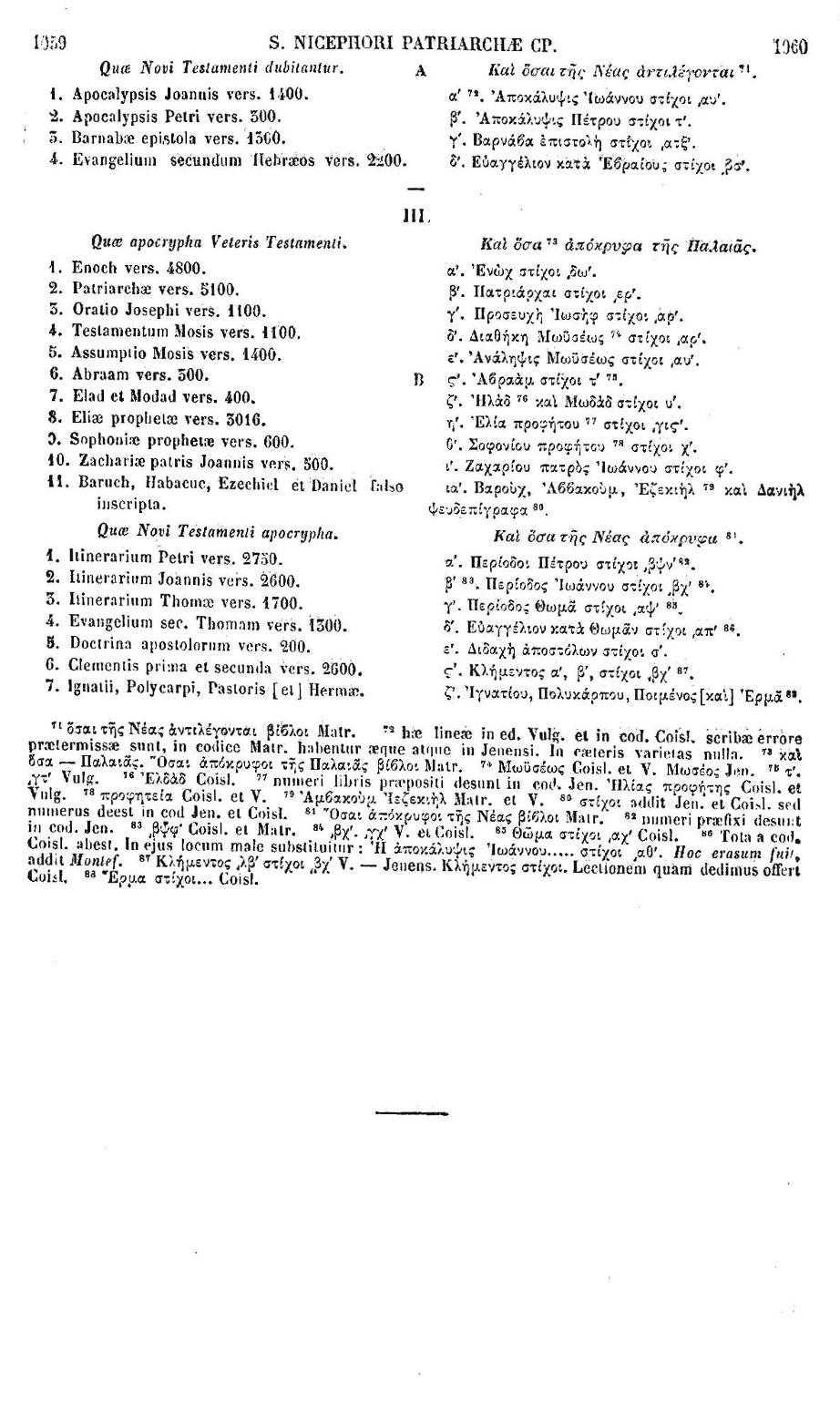

Here is how the Council of Trent enumerates and (purportedly) infallibly defines the Roman Catholic canon:

“The sacred and holy, ecumenical, and general Synod of Trent,–lawfully assembled in the Holy Ghost, the Same three legates of the Apostolic Sec presiding therein,–keeping this always in view, that, errors being removed, the purity itself of the Gospel be preserved in the Church; which (Gospel), before promised through the prophets in the holy Scriptures, our Lord Jesus Christ, the Son of God, first promulgated with His own mouth, and then commanded to be preached by His Apostles to every creature, as the fountain of all, both saving truth, and moral discipline; and seeing clearly that this truth and discipline are contained in the written books, and the unwritten traditions which, received by the Apostles from the mouth of Christ himself, or from the Apostles themselves, the Holy Ghost dictating, have come down even unto us, transmitted as it were from hand to hand; (the Synod) following the examples of the orthodox Fathers, receives and venerates with an equal affection of piety, and reverence, all the books both of the Old and of the New Testament–seeing that one God is the author of both –as also the said traditions, as well those appertaining to faith as to morals, as having been dictated, either by Christ’s own word of mouth, or by the Holy Ghost, and preserved in the Catholic Church by a continuous succession. And it has thought it meet [i.e.- proper] that a list of the sacred books be inserted in this decree, lest a doubt may arise in any one’s mind, which are the books that are received by this Synod. They are as set down here below: of the Old Testament: the five books of Moses, to wit, Genesis, Exodus, Leviticus, Numbers, Deuteronomy; Josue, Judges, Ruth, four books of Kings, two of Paralipomenon, the first book of Esdras, and the second which is entitled Nehemias; Tobias, Judith, Esther, Job, the Davidical Psalter, consisting of a hundred and fifty psalms; the Proverbs, Ecclesiastes, the Canticle of Canticles, Wisdom, Ecclesiasticus, Isaias, Jeremias, with Baruch; Ezechiel, Daniel; the twelve minor prophets, to wit, Osee, Joel, Amos, Abdias, Jonas, Micheas, Nahum, Habacuc, Sophonias, Aggaeus, Zacharias, Malachias; two books of the Machabees, the first and the second. Of the New Testament: the four Gospels, according to Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John; the Acts of the Apostles written by Luke the Evangelist; fourteen epistles of Paul the apostle, (one) to the Romans, two to the Corinthians, (one) to the Galatians, to the Ephesians, to the Philippians, to the Colossians, two to the Thessalonians, two to Timothy, (one) to Titus, to Philemon, to the Hebrews; two of Peter the apostle, three of John the apostle, one of the apostle James, one of Jude the apostle, and the Apocalypse of John the apostle. But if any one receive not, as sacred and canonical, the said books entire with all their parts, as they have been used to be read in the Catholic Church, and as they are contained in the old Latin vulgate edition; and knowingly and deliberately condemn the traditions aforesaid; let him be anathema. Let all, therefore, understand, in what order, and in what manner, the said Synod, after having laid the foundation of the Confession of faith, will proceed, and what testimonies and authorities it will mainly use in confirming dogmas, and in restoring morals in the Church.”

- General Council of Trent: Fourth Session, DECREE CONCERNING THE CANONICAL SCRIPTURES, link: https://www.papalencyclicals.net/councils/trent/fourth-session.htm

Such is the official list of Rome… and it’s backed by anathemas to boot!

Notice that there are a few different criteria for incurring those anathemas. According to Trent, one would have to knowingly and deliberately:

NOT receive the books as sacred (in ALL their parts as listed at Trent & contained in the old Latin vulgate edition).

NOT receive the books as canonical (in ALL their parts as listed at Trent & contained in the old Latin vulgate edition).1 2

As such, to evade falling under the anathema of Trent, it will not suffice for someone to receive the books listed as simply sacred in some sense. Similarly, it will not suffice to receive the books listed as simply canonical in some sense. Additionally, it will not suffice to receive most of the books listed as both sacred and canonical. To evade Trent’s anathema, one must fully receive each and every single one of its listed books entire in all their parts as both fully sacred and fully canonical.

This Tridentine list includes the following disputed books, which will be the focus of our article today: Tobit, Judith, Baruch, Ecclesiasticus, Wisdom, First and Second Maccabees.

Common Views of the Biblical Canon in Church History

Here, it might be worth mentioning some of the common views in regards to the canon in Church History:

There are, of course, those who have a 1-tier view of “Scripture” wherein any book that is considered “Scripture” must also be considered “canonical.” Some adherents to this view would see the Deuterocanonical books as fully Scriptural and as equally authoritative as the Protocanonical books; these adherents might hold that the canon of Scripture includes BOTH the 66 books included in Protestant Bibles and the 7 extra deuterocanonical books included in Roman Catholic Bibles (or, in some cases, including even more books than are found in Roman Catholic Bibles). However, other adherents to the 1-tier view would see the Deuterocanonical books as entirely apocryphal; these latter adherents might sometimes want to steer clear of the Deuterocanonical books entirely.

There are, of course, those who have a 2-tier view of “Scripture” wherein Scripture is composed of both “canonical” and “non-canonical” books. Those who hold this view see the “canonical” books of Scripture as sure, inerrant, and fully authoritative in all matters of life and doctrine. On the other hand, they see “non-canonical” books of Scripture as being of doubtful origin and composition, and thereby possessing a much lesser authority than the canonical books (if any at all); the non-canonical books of Scripture are primarily seen as being valuable for personal edification and devotion — but NOT for the establishing of doctrine nor the settling of controversy. Books which lay outside of these two tiers would be seen as apocryphal and not a part of Scripture.3

Both of the above positions have their nuances, and not every adherent to a particular view may always act perfectly consistently with their stated view; however, this is trivially true, as it is likewise the case with practically any position ever taken by imperfect human beings living in an imperfect world. Additionally, both of the above views have a category for “Apocryphal” writings which are not to be trusted by Christians (although this, too, is nuanced at times depending on the writer).

Broadly-speaking, our Roman Catholic friends land in the 1-tier view, whereas most magisterial Protestants would land in the 2-tier view. Due to the decentralized nature of Eastern Orthodoxy, it is hard to make all-encompassing statements about its positions on any given topic; however, it is worth noting that, both historically as well as in the modern day, significant segments of the Eastern Orthodox church have retained a nuanced 2-tier view. 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17

The Aim of This Article

With that in mind, the questions we are interested in exploring in this article are the following:

Is there a unanimous Patristic & Medieval consensus in favor of the Tridentine definition of the canon?18 19

Over the last couple of months, I have gathered a broad range of quotes from across church history that are relevant to this point (a special thank you to everyone who has aided me in this endeavor!). So, I thought it might be useful to others if I made a lengthy post documenting a significant number of them.

Now, before you read the rest of this article, please keep the following in mind: don’t expect a bunch of quotes that say “Hello! I affirm the exact Protestant canon.”20

That’s not what we’re after here.

The focus of this article is simply to try to figure out if church history is unanimously in support of the Tridentine definition of the canon.

*IMPORTANT NOTE: Please make sure to check out the copious footnotes throughout this article! In them, you can find added notes and context, alternate citations, the original Greek/Latin text, the source a given quote was pulled from, etc…

Patristic Quotes & Testimonies

AMPHILOCHIUS OF ICONIUM (c. 340-403 AD)

Historical/Biographical Details: 21

“But this especially for you to learn is fitting: not every book is safe which has acquired the venerable name of Scripture. For there appear from time to time pseudonymous books, some of which are intermediate or neighbours, as one might say, to the words of Truth, while others are spurious and utterly unsafe, like counterfeit and spurious coins which bear the king's inscription, but as regards their material are base forgeries. For this reason I will state for you the divinely inspired books one by one, so that you may learn them clearly. I will first recite those of the Old Testament. The Pentateuch has Creation [i.e. - Genesis], then Exodus, and Leviticus, the middle book, after which is Numbers, then Deuteronomy. Add to these Joshua, and Judges, then Ruth, and of Kingdoms the four books, and the double team of Chronicles; after these, Esdras, one and then the second. Then I would review for you five in verse: Job, crowned in the contests of many sufferings, and the Book of Psalms, soothing remedy for the soul, three of Solomon the Wise: Proverbs, Ecclesiastes, Canticle of Canticles. Add to these the Prophets Twelve, Hosea first, then Amos the second, Micah, Joel, Obadiah, and the type of Him who three days suffered, Jonah, Nahum after those, and Habakkuk; and ninth, Zephaniah, Haggai, and Zechariah, and twice-named angel Malachi. After these prophets learn yet another four: The great and fearless Isaiah, the sympathetic Jeremiah, and mysterious Ezekiel, and finally Daniel, most wise in his deeds and words. With these, some approve the inclusion of Esther. Time now for me to recite the books of the New Testament. Accept only four Evangelists, Matthew, then Mark, to which Luke as third add; count John in time as fourth, but first in sublimity of dogma. Son of Thunder rightly he is called, who loudly sounded forth the Word of God. Accept from Luke a second book also, that of the catholic Acts of the Apostles. Add to these besides that Chosen Vessel, Herald of the Gentiles, the Apostle Paul, writing in wisdom to the churches twice seven epistles, one to the Romans, to which must be added two to the Corinthians, and that to the Galatians, and to the Ephesians, after which there is the one to the Philippians, then those written to the Colossians, to the Thessalonians two, two to Timothy, and to Titus and Philemon one each, and to the Hebrews one. Some call that to the Hebrews spurious, but they say it not well; for the grace is genuine. some say seven, others only three must be accepted: one of James, one of Peter, one of John, otherwise three of John, and with them two of Peter, and also Jude's, the seventh. The Apocalypse of John, again, some approve, but most will call it spurious. This would be the most unerring canon of the divinely inspired scriptures.”22 23 24

- Amphilochius of Iconium, Iambi ad Seleucum, Vol. 37 of Migne's Patrologia Graeca, link: https://www.bible-researcher.com/amphilocius.html

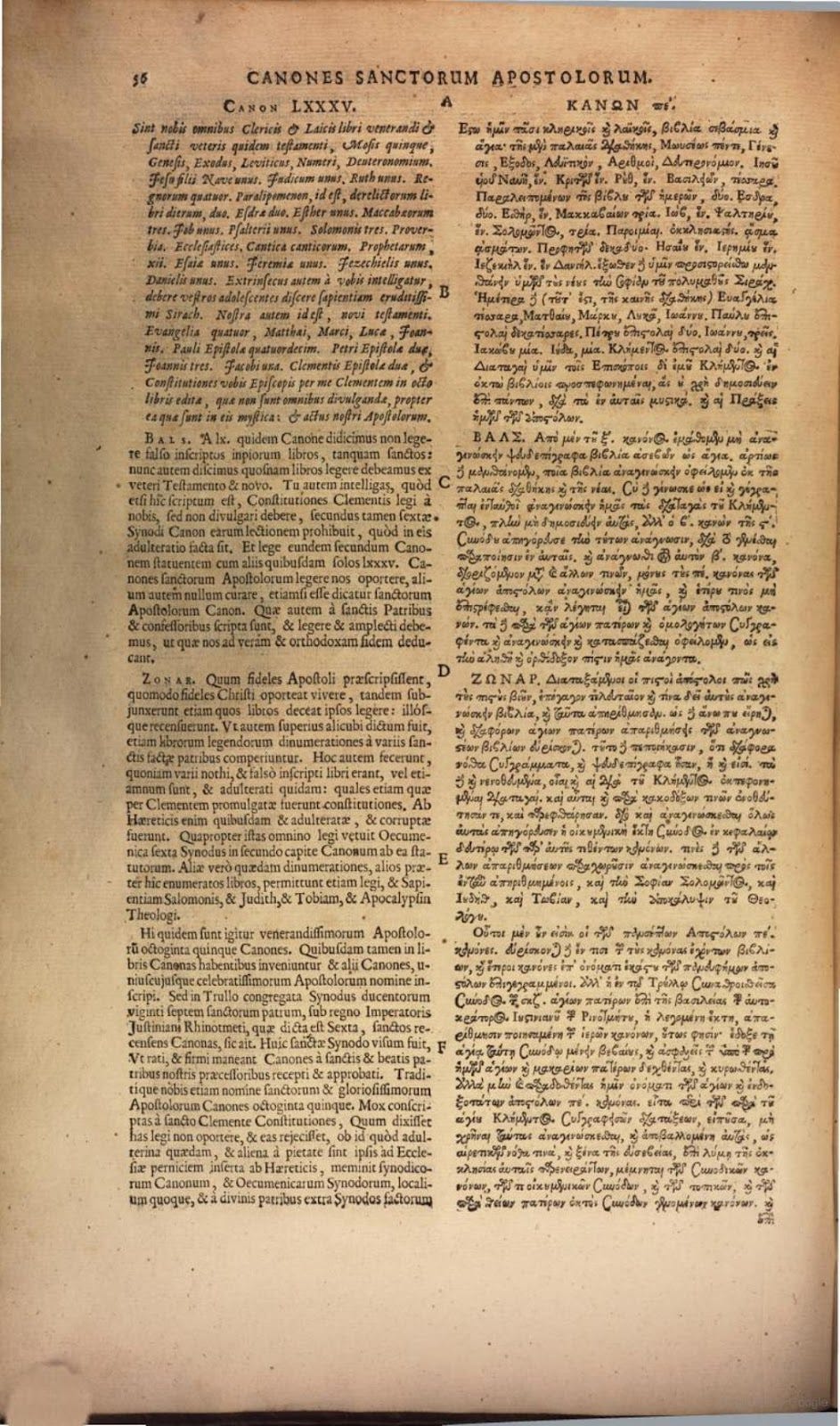

APOSTOLIC CANONS (c. 380 AD)

Historical/Biographical Details: 25 26 27

“Canon 85: Concerning Holy Scripture.

Let the following books be esteemed venerable and holy by all of you, both clergy and laity. Of the Old Testament: the five books of Moses, Genesis, Exodus, Leviticus, Numbers, and Deuteronomy; one of Joshua the son of Nun; one of the Judges; one of Ruth; four of the Kings; two of Paralipomena (the books of Chronicles); two of Ezra [i.e.- Ezra and Nehemiah]; 2 one of Esther; one of Judith;* three of the Maccabees; one of Job; the one hundred and fifty Psalms; three books of Solomon: Proverbs, Ecclesiastes, Song of Songs; the sixteen of the Prophets. And see that those newly come to discipleship become acquainted with the Wisdom of the learned Sirach [i.e.- Ecclesiasticus]. And ours, that is, of the New Testament, are the four Gospels, of Matthew, Mark, Luke, John; the fourteen epistles of Paul; two epistles of Peter; three of John; one of James; one of Jude; two epistles of Clement; and the Constitutions dedicated to you, the bishops, by me, Clement, in eight books, which it is not appropriate to make public before all, because of the mysteries contained in them; and the Acts of us, the Apostles.”28 29 30

- Apostolic Canons, Canon 85, B.F. Westcott, General Survey of the History of the Canon of the New Testament (Seventh Edition), London: Macmillan & Co. (1896), Appendix D, pg. 551, link: https://archive.org/details/generalsurveyofh00westuoft/page/551/mode/1up

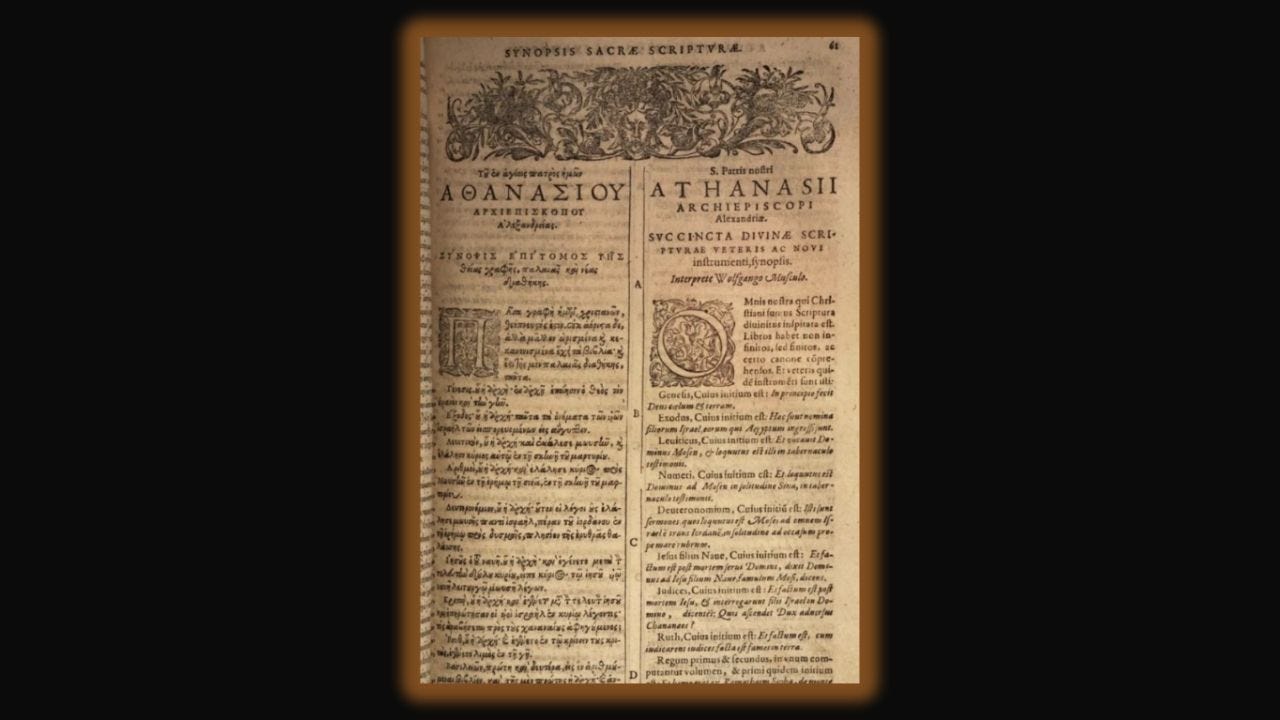

ATHANASIUS OF ALEXANDRIA (c. 296-373 AD)

Historical/Biographical Details: 31 32

“In proceeding to make mention of these things, I shall adopt, to commend my undertaking, the pattern of Luke the Evangelist, saying on my own account: 'Forasmuch as some have taken in hand Luke 1:1,' to reduce into order for themselves the books termed apocryphal, and to mix them up with the divinely inspired Scripture, concerning which we have been fully persuaded, as they who from the beginning were eyewitnesses and ministers of the Word, delivered to the fathers; it seemed good to me also, having been urged thereto by true brethren, and having learned from the beginning, to set before you the books included in the Canon, and handed down, and accredited as Divine; to the end that any one who has fallen into error may condemn those who have led him astray; and that he who has continued steadfast in purity may again rejoice, having these things brought to his remembrance. There are, then, of the Old Testament, twenty-two books in number; for, as I have heard, it is handed down that this is the number of the letters among the Hebrews; their respective order and names being as follows. The first is Genesis, then Exodus, next Leviticus, after that Numbers, and then Deuteronomy. Following these there is Joshua, the son of Nun, then Judges, then Ruth. And again, after these four books of Kings, the first and second being reckoned as one book, and so likewise the third and fourth as one book. And again, the first and second of the Chronicles are reckoned as one book. Again Ezra, the first and second are similarly one book. After these there is the book of Psalms, then the Proverbs, next Ecclesiastes, and the Song of Songs. Job follows, then the Prophets, the twelve being reckoned as one book. Then Isaiah, one book, then Jeremiah with Baruch, Lamentations, and the epistle, one book; afterwards, Ezekiel and Daniel, each one book. Thus far constitutes the Old Testament. Again it is not tedious to speak of the [books] of the New Testament. These are, the four Gospels, according to Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John. Afterwards, the Acts of the Apostles and Epistles (called Catholic), seven, viz. of James, one; of Peter, two; of John, three; after these, one of Jude. In addition, there are fourteen Epistles of Paul, written in this order. The first, to the Romans; then two to the Corinthians; after these, to the Galatians; next, to the Ephesians; then to the Philippians; then to the Colossians; after these, two to the Thessalonians, and that to the Hebrews; and again, two to Timothy; one to Titus; and lastly, that to Philemon. And besides, the Revelation of John. These are fountains of salvation, that they who thirst may be satisfied with the living words they contain. In these alone is proclaimed the doctrine of godliness. Let no man add to these, neither let him take ought from these. For concerning these the Lord put to shame the Sadducees, and said, 'You err, not knowing the Scriptures.' And He reproved the Jews, saying, 'Search the Scriptures, for these are they that testify of Me (Matthew 22:29; John 5:39)' But for greater exactness I add this also, writing of necessity; that there are other books besides these not indeed included in the Canon, but appointed by the Fathers to be read by those who newly join us, and who wish for instruction in the word of godliness. The Wisdom of Solomon, and the Wisdom of Sirach, and Esther, and Judith, and Tobit, and that which is called the Teaching of the Apostles, and the Shepherd. But the former, my brethren, are included in the Canon, the latter being [merely] read.”33 34

- St. Athanasius, NPNF2-04, Festal Letter 39, link: https://www.newadvent.org/fathers/2806039.htm

AUGUSTINUS HIBERNICUS - A.K.A: THE IRISH AUGUSTINE (7th CENTURY AD)

Historical/Biographical Details: 35

“Even if it turns out that a number of miraculous events described in the books of Maccabees could be included in our study, we will not address them, because we intended to focus only on the miracles contained in the canonical books.”

- Augustinus Hibernicus, VIIe, De mirabilibus sacrae scripturae 2.34, Patrologia Latina 35:2192, link: https://books.google.com/books?id=LvIQAAAAYAAJ&printsec=frontcover&source=gbs_ge_summary_r&cad=0#v=onepage&q=2192&f=true

“As for what Habakkuk translated in the fables of Belle and the Dragon, we have not included them in our study because they do not have the authority of divine scripture.”

- Augustinus Hibernicus (The Irish Augustine), VIIe, De mirabilibus sacrae scripturae 2.32, Patrologia Latina 35:2191, link: https://books.google.com/books?id=LvIQAAAAYAAJ&printsec=frontcover&source=gbs_ge_summary_r&cad=0#v=onepage&q=2192&f=true

BASIL THE GREAT - A.K.A: BASIL OF CAESAREA (c. 330-379 AD)

Historical/Biographical Details: 36 37

“As we are dealing with numbers and every number among real existencies a certain significance of which the Creator of the universe made full use as well in the general scheme as in the arrangement of the details, we must give good heed, and with the help of the Scriptures trace their meaning, and the meaning of each of them. Nor must we fail to observe that without reason the canonical books are twenty-two, according to the Hebrew tradition, the same in number as the letters of the Hebrew alphabet. For as the twenty-two letters may be regarded as an introduction to the wisdom and the Divine doctrines given to men in those characters, so the twenty-two inspired books are an alphabet of the wisdom of God and an introduction to the knowledge of realities.”

- Basil the Great, Philocalia, Chapter III, Why the inspired books are twenty-two in number. From the same volume on the 1st Psalm. George Lewis, trans., The Philocalia of Origen: A Compilation of Selected Passages from Origen’s Works made by St. Gregory of Nazianzus and St. Basil of Caesarea (Edinburgh: T. & T. Clark, 1911), p. 34. See also Origen, Philocalie, ch. 3, edited by Marguerite Harl, Sources Christiennes 302 (Paris: Cerf, 1983), p. 260.

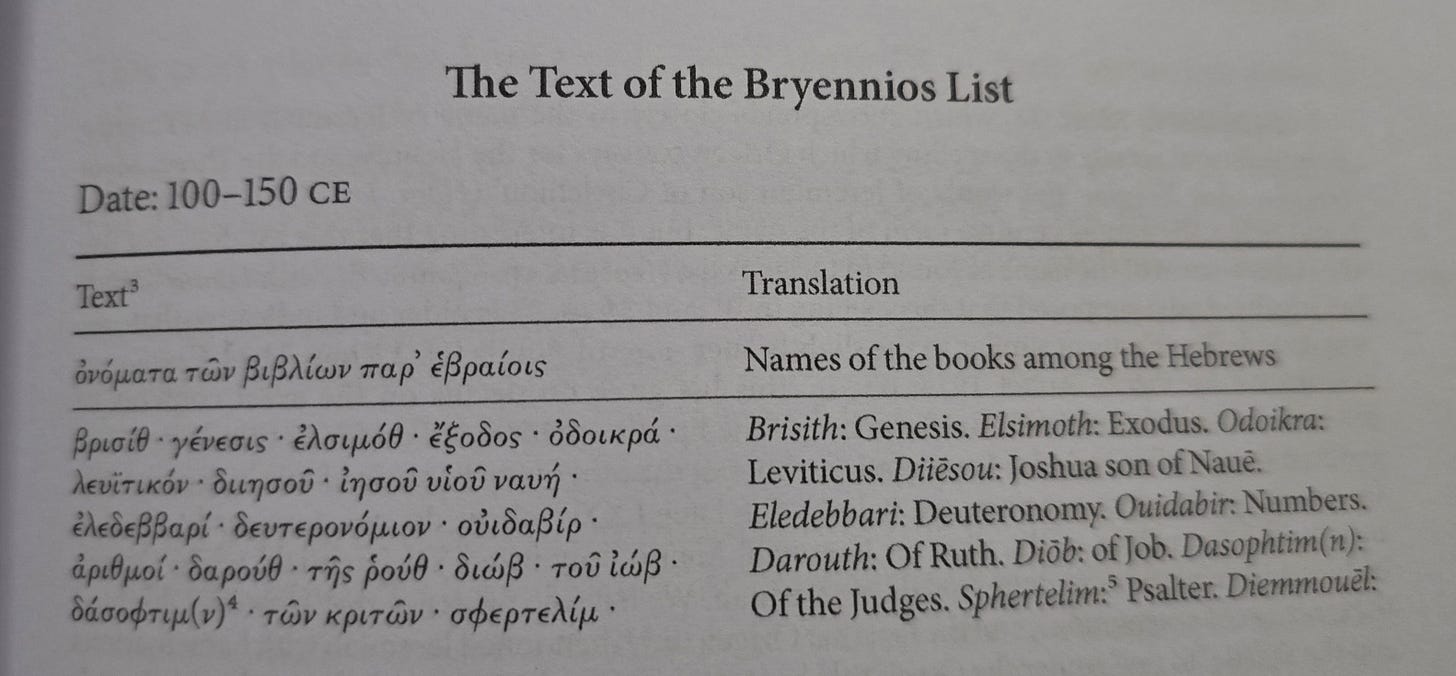

BRYENNIOS LIST (2nd CENTURY AD)

Historical/Biographical Details: 38

“Names of the books among the Hebrews.

Brisith: Genesis. Elsimoth: Exodus. Odoikra: Leviticus. Diiēsou: Joshua son of Nauē. Eledebbari: Deuteronomy. Ouidabir: Numbers. Darouth: Of Ruth. Diōb: of Job. Dasophtim(n): Of the Judges. Sphertelim: Psalter. Diemmouēl: Of Kingdoms First. Diaddoudemouēl: Of Kingdoms Second. Damalachēm: Of Kingdoms Third. Amalachēm: Of Kingdoms Fourth. Debriiamin: Of Paralipomena First. Of Paralipomena Second. Damaleōth: Of Proverbs. Dakoloeth: Ecclesiastes. Sira Sirim: Song of Songs. Dierem: Jeremiah. Daatharsiar: Twelve Prophets. Dēsaiou: Of Isaiah. Dieezekiēl: Of Ezekiel. Dadaniēl: Of Daniel. Desdra: Esdras A. Dadesdra: Esdras B. Desthēs.”39 40 41

- Bryennios List, translated by Edmon Gallagher and John Meade, The Biblical Canon Lists from Early Christianity: Texts and Analysis, Oxford University Press (2017), pg. 71-72.

COUNCIL OF LAODICEA (AD 363)

Historical/Biographical Details: 42 43

“Let no private psalms nor any uncanonical books be read in church, but only the canonical ones of the New and Old Testament. It is proper to recognize as many books as these: of the Old Testament, 1. the Genesis of the world; 2. the Exodus from Egypt; 3. Leviticus; 4. Numbers; 5. Deuteronomy; 6. Joshua the son of Nun; 7. Judges and Ruth; 8. Esther; 9. First and Second Kings [i.e. First and Second Samuel]; 10. Third and Fourth Kings [i.e. First and Second Kings]; 11. First and Second Chronicles; 12. First and Second Ezra [i.e. Ezra and Nehemiah]; 13. the book of one hundred and fifty Psalms; 14. the Proverbs of Solomon; 15. Ecclesiastes; 16. Song of Songs; 17. Job; 18. the Twelve [minor] Prophets; 19. Isaiah; 20. Jeremiah and Baruch, Lamentations and the Epistle [of Jeremiah]; 21. Ezekiel; 22. Daniel.”44 45 46

- Council of Laodicea, translated from the Greek as presented in B.F. Westcott, A General Survey of the History of the Canon of the New Testament (5th ed. Edinburgh, 1881), link: https://www.bible-researcher.com/laodicea.html47

CYRIL OF JERUSALEM (315-386 AD)

Historical/Biographical Details: 48

“Learn also diligently, and from the Church, what are the books of the Old Testament, and what those of the New. And, pray, read none of the apocryphal writings : for why do you, who know not those which are acknowledged among all, trouble yourself in vain about those which are disputed? Read the Divine Scriptures, the twenty-two books of the Old Testament, these that have been translated by the Seventy-two Interpreters. For after the death of Alexander, the king of the Macedonians, and the division of his kingdom into four principalities, into Babylonia, and Macedonia, and Asia, and Egypt, one of those who reigned over Egypt, Ptolemy Philadelphus, being a king very fond of learning, while collecting the books that were in every place, heard from Demetrius Phalereus, the curator of his library, of the Divine Scriptures of the Law and the Prophets, and judged it much nobler, not to get the books from the possessors by force against their will, but rather to propitiate them by gifts and friendship; and knowing that what is extorted is often adulterated, being given unwillingly, while that which is willingly supplied is freely given with all sincerity, he sent to Eleazar, who was then High Priest, a great many gifts for the Temple here at Jerusalem, and caused him to send him six interpreters from each of the twelve tribes of Israel for the translation. Then, further, to make experiment whether the books were Divine or not, he took precaution that those who had been sent should not combine among themselves, by assigning to each of the interpreters who had come his separate chamber in the island called Pharos, which lies over against Alexandria, and committed to each the whole Scriptures to translate. And when they had fulfilled the task in seventy-two days, he brought together all their translations, which they had made in different chambers without sending them one to another, and found that they agreed not only in the sense but even in words. For the process was no word-craft, nor contrivance of human devices: but the translation of the Divine Scriptures, spoken by the Holy Ghost, was of the Holy Ghost accomplished. Of these read the two and twenty books, but have nothing to do with the apocryphal writings. Study earnestly these only which we read openly in the Church. Far wiser and more pious than yourself were the Apostles, and the bishops of old time, the presidents of the Church who handed down these books. Being therefore a child of the Church, trench thou not upon its statutes. And of the Old Testament, as we have said, study the two and twenty books, which, if you are desirous of learning, strive to remember by name, as I recite them. For of the Law the books of Moses are the first five, Genesis, Exodus, Leviticus, Numbers, Deuteronomy. And next, Joshua the son of Nave , and the book of Judges, including Ruth, counted as seventh. And of the other historical books, the first and second books of the Kings are among the Hebrews one book; also the third and fourth one book. And in like manner, the first and second of Chronicles are with them one book; and the first and second of Esdras are counted one. Esther is the twelfth book; and these are the Historical writings. But those which are written in verses are five, Job, and the book of Psalms, and Proverbs, and Ecclesiastes, and the Song of Songs, which is the seventeenth book. And after these come the five Prophetic books: of the Twelve Prophets one book, of Isaiah one, of Jeremiah one, including Baruch and Lamentations and the Epistle ; then Ezekiel, and the Book of Daniel, the twenty-second of the Old Testament. Then of the New Testament there are the four Gospels only, for the rest have false titles and are mischievous. The Manichæans also wrote a Gospel according to Thomas, which being tinctured with the fragrance of the evangelic title corrupts the souls of the simple sort. Receive also the Acts of the Twelve Apostles; and in addition to these the seven Catholic Epistles of James, Peter, John, and Jude; and as a seal upon them all, and the last work of the disciples, the fourteen Epistles of Paul. But let all the rest be put aside in a secondary rank. And whatever books are not read in Churches, these read not even by yourself, as you have heard me say. Thus much of these subjects.”49 50

- Cyril of Jerusalem, Catechetical Lecture 4, 33-36, link: https://www.newadvent.org/fathers/310104.htm

DIALOGUE BETWEEN TIMOTHY THE CHRISTIAN AND AQUILA THE JEW (c. 2nd, 3rd, OR 6th CENTURY AD)

Historical/Biographical Details: 51

“[Timothy the Christian said:] These, then, are the divinely inspired books, both among Christians and among Hebrews. The first is the book of Genesis. The second is Exodus. The third is Leviticus. The fourth is Numbers. These are the ones dictated through the mouth of God and written by the hand of Moses. And the fifth is the Book of Deuteronomy, not dictated though the mouth of God but was the law given a second time through Moses. (Therefore, it was not placed in the aron, that is, the Ark of the Covenant) (see Deut. 31:9; 24-26). This is the Mosaic Pentateuch. The sixth is Joshua, son of Nun. The seventh is the Judges along with Ruth. The eighth book is the ‘Things that are left,’ first and second (1,2 Chronicles). Ninth is the Book of Kingdoms, first and second (1,2 Samuel). Tenth is the third and fourth Book of Kingdoms (1,2 Kings). Eleventh is Job. Twelfth is the Psalter of David. Thirteenth is the Proverbs of Solomon. Fourteenth is Ecclesiastes along with the Canticles. Fifteenth is the Twelve Prophets, then Isaiah, Jeremiah. And again, Ezekiel, then Daniel and again, Esdras (Ezra-Nehemiah), twentieth. The twenty first is the book of Judith. Twenty second is Esther. For Tobit and the Wisdom of Solomon and the Wisdom of Jesus Son of Sirach, the 72 translators (LXX) handed down to us as apocryphal books. These twenty two books are the inspired and canonical ones. There are twenty seven, but are numbered as twenty two, because five of them are doubled. And they are numbered according to the letters of the Hebrew alphabet, and all the rest of them belong to the Apocrypha.”52

- Dr. William Warner, A Translation of the Dialogue of Timothy and Aquila, 3.11a-3.18, link: https://www.academia.edu/11087040/Dialogue_of_Timothy_and_Aquila

GREGORY OF NAZIANZUS (329-390 AD)

Historical/Biographical Details: 53 54 55

“Receive the number and names of the holy books. First the twelve historical books in order: first is Genesis, then Exodus, Leviticus, Numbers and the testament of the law repeated again; Joshua, Judges and Ruth the Moabitess follow these; after this the famous deeds of Kings holds the ninth and tenth place; the Chronicles comes in the eleventh place, and Ezra is last. There are also five poetic books, first of which is Job, the one next to it is King David’s, and three of Solomon, namely Ecclesiastes, Proverbs, and his Song. After these come five books of the holy prophets, of which twelve are contained in one volume: Hosea…Malachi, these are in the first book; the second contains Isaiah. After these is Jeremiah, called from his mother’s womb, then Ezekiel, strength of the Lord, and Daniel last. These twenty-two books of the Old Testament are counted according to the twenty-two letters of the Jews…Let not your mind be deceived about extraneous books (for many false ascriptions are making the rounds), but you should hold to this legitimate number from me, dear reader.”

- Gregory of Nazianzus, Carmina Dogmatica, Book I, Section I, Carmen XII. PG 37:471-474. Translation by Dr. Michael Woodward, Associate Library Director, Archbishop Vehr Theological Library. See also William Jurgens, The Faith of the Early Fathers, Volume 2, p. 42.

GREGORY THE GREAT - BISHOP OF ROME (c. 540-604)

Historical/Biographical Details: 56 57

“Whence it is needful with great diligence both always to be doing good things, and to keep ourselves heedfully in the thought of the heart from the very good things themselves, lest, if they uplift the mind, they be not good, which are enlisted not to the Creator, but to pride. With reference to which particular we are not acting irregularly, if from the books, though not Canonical, yet brought out for the edifying of the Church, we bring forward testimony. Thus Eleazar in the battle smote and brought down an elephant, but fell under the very beast that he killed. 1 Macc. 6:46.”58 59

- Gregory the Great, Morals On The Book Of Job, Book XIX, link: https://www.ecatholic2000.com/job/untitled-31.shtml#_Toc385932145

EPIPHANIUS OF SALAMIS - A.K.A: EPIPHANIUS OF CONSTANTIA (310-403 AD)

Historical/Biographical Details: 60

“Now, at the time of the return from the Babylonian captivity, these Jews had books and these (following) prophets and these (following) books of prophets: first Genesis, second Exodus, third Leviticus, fourth Numbers, fifth Deuteronomy, sixth Book of Joshua of Naue, seventh of Judges, eighth of Ruth, ninth of Job, tenth the Psalter, eleventh Proverbs of Solomon, twelfth Ecclesiastes, thirteenth the Song of Songs, fourteenth first of Kingdoms, fifteenth second of Kingdoms, sixteenth third of Kingdoms, seventeenth fourth of Kingdoms, eighteenth first of Paralipomenon, nineteenth second of Paralipomenon, twentieth the Twelve Prophets, twenty-first Isaiah the prophet, twenty-second Jeremiah the prophet with the Lamentations and Epistles, both his own and Baruch's, twenty-third Ezekiel the prophet, twenty-fourth Daniel the prophet, twenty-fifth Esdras I, twenty-sixth Esdras II, twenty-seventh Esther. These are the twenty-seven books given by God to the Jews; now these are numbered twenty-two just as their letters in Hebrew characters because ten books are double, being reckoned as five. Now we have spoken clearly concerning this in another place. Now they also have two other books in dispute, the Wisdom of Sirach and the one of Solomon, separate from some other apocryphal books.”

- Epiphanius of Salamis, Panarion 8.6.1-4, Edmon L. Gallagher and John D. Meade, The Biblical Canon Lists from Early Christianity: Texts and Analysis (Oxford, 2017), pp. 160-161.

“For if you were begotten from the Holy Spirit and instructed in the prophets and apostles, you must have gone through (the record) from the beginning of the genesis of the world until the times of Esther in twenty-seven books of the Old Covenant, which are numbered as twenty-two, and in the four holy gospels, and in fourteen epistles of the holy apostle Paul, and in the general epistles of James, Peter, John, and Jude before these [and] with the Acts of the Apostles in their times, and in the Revelation of John, and in the Wisdom books, I mean of Solomon and of the son of Sirach, and in short having gone through all the Divine Scriptures, I say, you should have condemned yourself for bringing forward as not unfitting for God but actually pious towards God a word which is nowhere listed, the word ‘unbegotten’ (ἀγεννητός), nowhere mentioned in Divine Scripture.”

- Epiphanius of Salamis, Panarion 76.22.5, Edmon L. Gallagher and John D. Meade, The Biblical Canon Lists from Early Christianity: Texts and Analysis (Oxford, 2017), pp. 168-169

“The book of the Genesis of the World to one pair, the Exodus of the Israelites to another pair, that of Leviticus to another, and the next book in order to the next; and thus were translated the twenty-seven recognized canonical books, but twenty-two when counted according to the letters of the alphabet of the Hebrews. For the names of the letters are twenty-two. But there are five of them that have a double form, for k has a double form, and m and n and p and s. Therefore in this manner the books also are counted as twenty-two; but there are twenty-seven, because five of them are double. For Ruth is joined to Judges, and they are counted among the Hebrews (as) one book. The first (book) of Kingdoms is joined to the second and called one book; the third is joined to the fourth and becomes one book. First Paraleipomena is joined to Second and called one book. The first book of Ezra is joined to the second and becomes one book. So in this way the books are grouped into four "pentateuchs," and there are two others left over, so that the books of the (Old) Testament are as follows: the five of the Law—Genesis, Exodus, Leviticus, Numbers, Deuteronomy—this is the Pentateuch, otherwise the code of law; and five in verse----the book of Job, then of the Psalms, the Proverbs of Solomon, Koheleth, the Song of Songs. Then another "pentateuch" (of books) which are called the Writings, and by some the Hagiographa, which are as follows: Joshua the (son) of Nun, the book of Judges with Ruth, First and Second Paraleipomena, First and Second Kingdoms, Third and Fourth Kingdoms; and this is a third "pentateuch." Another "pentateuch" is the books of the prophets—the Twelve Prophets (forming) one book, Isaiah one, Jeremiah one, Ezekiel one, Daniel one—and again the prophetic "pentateuch" is filled up. But there remain two other books, which are (one of them) the two of Ezra that are counted as one, and the other the book of Esther. So twenty-two books are completed according to the number of the twenty-two letters of the Hebrews. For there are two (other) poetical books, that by Solomon called "Most Excellent," and that by Jesus the son of Sirach and grandson of Jesus—for his grandfather was named Jesus (and was) he who composed Wisdom in Hebrew, which his grandson, translating, wrote in Greek—which also are helpful and useful, but are not included in the number of the recognized; and therefore they were not kept in the chest, that is, in the ark of the covenant. But, further, this also should not escape you, O lover of the good, that the Hebrews have also divided the book of Psalms into five books, so that it is yet another "pentateuch." For from the first Psalm to the fortieth they reckon one book, and from the forty-first to the seventy-first they reckon a second; from the seventy-second to the eighty-eighth they make the third book; for the eighty-ninth to the one hundred fifth they make the fourth; from the one hundred sixth to the one hundred fiftieth they unite into the fifth. For every Psalm that had as its conclusion, "Blessed be the Lord, so be it, so be it," they thought to be appropriately the end of a book. And this is found in the fortieth and in the seventy-first and in the eighty-eighth and in the one hundred fifth, and (thus) the four books are completed. But the conclusion of the fifth book, instead of the "Blessed be the Lord, so be it, so be it," is "Let everything that breathes praise the Lord! Hallelujah!" For when they thus reckoned they thereby completed the whole matter. Thus they are twenty-seven; but they are counted as twenty-two, even with the book of Psalms and those by Jeremiah—I mean Lamentations and the epistles of Baruch and of Jeremiah, although the epistles are not in use among the Hebrews, but only Lamentations, which is joined to Jeremiah. In the way we have related they were translated. They were given to every pair of translators in rotation, and again from the first pair to the second, and from the second pair to the third; and thus they went, every one going around. And they were translated thirty-six times, as the story goes, both the twenty-two and the seventy-two that are apocryphal.”

- Epiphanius of Salamis, (The Treatise) of St. Epiphanius, Bishop of the City of Constantia in Cyprus, on Measures and Weights and Numbers and Other Things That Are in the Divine Scriptures, link: https://www.ccel.org/ccel/pearse/morefathers/files/epiphanius_weights_03_text.htm61

“... On account of which the letters of the Hebrews are also twenty-two, which are these: Aleph, Bēth, Gimēl, Deled, Ē, Ouau, Zēth, Ēth, Tēth, Iōth, Chaph, Lamed, Mēm, Noun, Samech, Aїn, Phē, Sadē, Kōph, Rēs, Sin, Thau. Wherefore also there are twenty-two specified books of the Old Covenant, although on the one hand the Hebrews have twenty-seven (books) but on the other hand they are numbered as twenty-two since five of their letters are double: the Chaph is double, and the Mem, and the Noun, and the Phi, and the Sadi. For in this way the books are numbered. First, Birsēth, which is called Genesis of the World. Elēsimath, the Exodus of the Sons of Israel out of Egypt. Ouaїekra, which is translated Leviticus. Ouaїdabēr, which is Numbers. Elledebareim, Deuteronomy. Diēsou, the one of Joshua son of Naue. Diōb, the one of Job. Desōphteim, the one of the Judges. Derouth, the one of Ruth. Spherteleim, the Psalter. Debriiamein, the first of the Paralipomenon. Debriiamein, second of Paralipomenon. Desamouēl, first of Kingdoms. Dadoudesamouēl, second of Kingdoms. Dmalacheim, third of Kingdoms. Dmalacheim, fourth of Kingdoms. Dmethalōth, the one of Proverbs. Dekōeleth, Ecclesiastes Sirathsirein, the Song of Songs. Dathariasara, the Twelve Prophets. Dēsaїou, of the prophet Isaiah. Dieremiou, the one of Jeremiah. Diezekēl, the one of Ezekiel. Dedaniēl, the one of Daniel. Desdra, the one of first Esdras. Desdra, the one of second Esdras. Desthēr, the one of Esther. Now these twenty-seven books are numbered as twenty-two according to the number of the letters, since also five letters are double, just as we said above. And there is another small book, which is called Kinōth, which is translated Lamentations of Jeremiah. This one is joined to Jeremiah, which is beyond the number and joined to Jeremiah.”

- Epiphanius of Salamis, Of Measures and Weights 22-23, Edmon L. Gallagher and John D. Meade, The Biblical Canon Lists from Early Christianity: Texts and Analysis (Oxford, 2017), pp. 166-167.

HILARY OF POITIERS (c. 310-367 AD)

Historical/Biographical Details: 62 63

“The law of the Old Testament is reckoned in twenty-two books, that they might fit the number of Hebrew letters. They are counted according to the tradition of the ancient fathers, so that those of Moses are five books; the sixth of Joshua; the seventh of Judges and Ruth; the eighth of the first and second of Kings; the tenth of the two books called the Chronicles; the eleventh of Ezra, (wherein Nehemiah was comprehended:) the book of Psalms made the twelfth; the Proverbs of Solomon, Ecclesiastes, and the Song of Songs, made the thirteenth, fourteenth, and fifteenth; the twelve prophets made the sixteenth; then Isaiah, and Jeremy, together with his Lamentations and his Epistle, (now the twenty-ninth chapter of his prophecy) Daniel, and Ezekiel, and Job, and Esther, made up the full number of twenty-two books.”64 65 66 67

- Hilary of Poitiers, Sancti Hilarii Pictaviensis Episcopi Tractatus Super Psalmos, Prologue 15, Testamenti Veteris libri XXII, aut 24. Tres linguae praecipuae. Patrologia Latina 9:241. Translation by Dr. Michael Woodward, Associate Library Director, Archbishop Vehr Theological Library.

JAMES OF EDESSA (c. 640-708 AD)

Historical/Biographical Details: 68

“It is indeed true that St. Clement, a disciple of the Apostle Peter, wrote in the Eighth Constitution (διάταξις) regarding the canons, as your Fraternity has written, that there are five books of Solomon, but he does not distinguish and name clearly which those books are; while there are only three according to the holy doctors that you have mentioned: Athanasius, Basil, Gregory, Amphilochius, and, before them, Eusebius of Caesarea, with many others who followed them. [...] These words embarrassed and surprised you, so you now ask me — although I am as embarrassed and as surprised as you — why Clement said five, while the Doctors said three, a fact which is true and absolutely true, but which I do not understand and do not promise to explain. I only write what I think is correct, which at least has a semblance of truth. So I hasten to say that Clement counted five books of Solomon because he assigned to him also the Wisdom, that admirable book, and because he divided the book of Proverbs into two books, because some also share the idea that these are two books that were collected and placed together, starting at the place where are mentioned the Proverbs written by “friends” of Hezekiah, until the end. That’s what I think that I can say about the text of Clement. As to the text of the doctors who mentions only three books (of Solomon), I say they do have three, because they speak only of the books defined canonically by the Church as proto-canonical books, and because they make only one book and not two of the whole book of Proverbs. All these ideas derive from my limited and humble opinion; as for the real truth, we leave that to be learned from the Spirit, the writer of the (holy) books; however, for your Fraternity’s tranquillity and comfort, I thought that I would send you with this a copy of a small treatise that I wrote about the Wisdom, this book so admirable that many attribute it to Solomon, from the time when I was applying myself with love of work to revise this book with the others. That’s all for the first question in your Fraternity’s letter. Let’s look at the second question: Why are these books not counted among the canonical books of the Church? I speak of the great Wisdom and of Jesus son of Sirach, and of many others which are rejected, like Tobit and those of the women Esther and Judith, and the three (books) on the Maccabees. I will answer again, that the truth is exactly known to the prophetic, apostolic and learned Spirit. I also would like to tell you the opinion of my feeble intelligence: it is that they are not entirely composed of words revealed by the (Holy) Spirit or of prophecies from God, but that they contain either words of human wisdom written by pious men, or stories about holy and pious men themselves, which is why they were separated from the number of the canonical books of the Church, and were placed for special reading outside of the (books) for regular use in the correction and correcting of morals, actions and deeds, for those who are of a very teachable spirit, and want to hear some useful and loving advice for word and deed and for the knowledge of good conduct.”69

- James of Edessa, Letter to John the Stylite, English translation from the French of Francois Nau in ROC, link: https://www.roger-pearse.com/weblog/tag/james-of-edessa/70

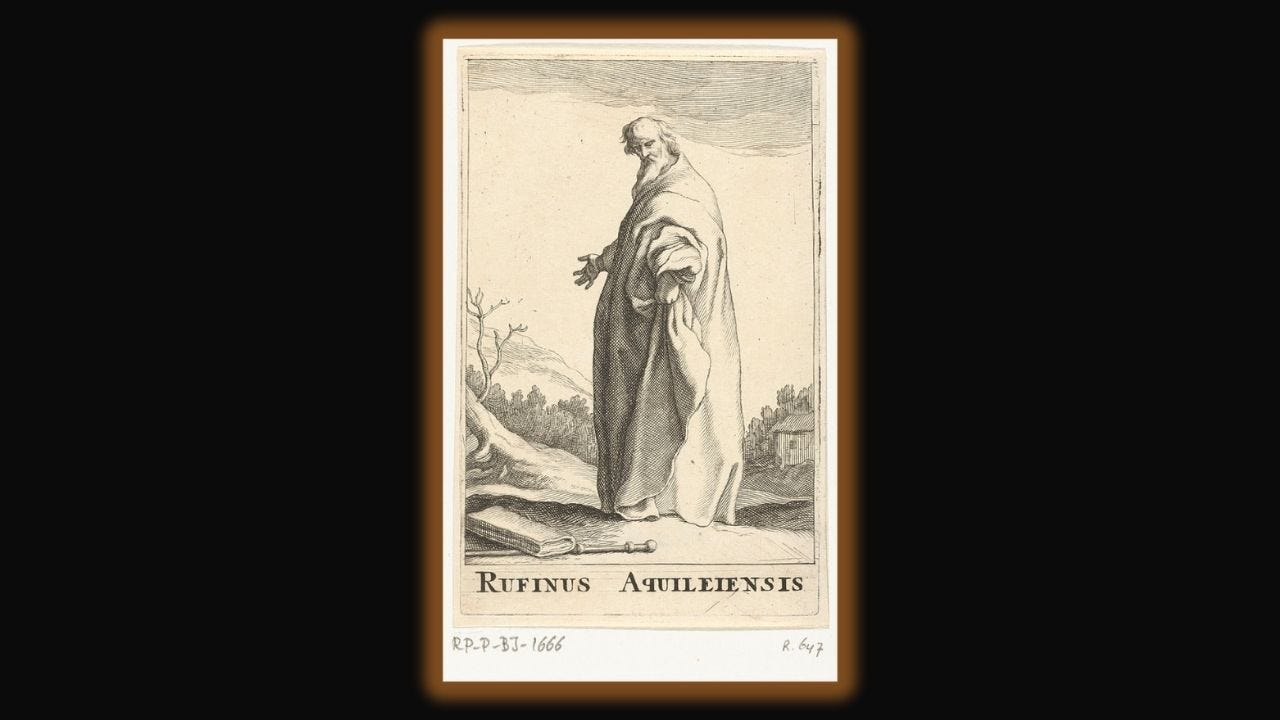

JEROME OF STRIDON (347-420 AD)

Historical/Biographical Details: 71 72

Historical Context on Jerome’s Reception: 73

“That the Hebrews have twenty-two letters is testified also by the Syrian and Chaldaaen languages, which for the most part correspond to the Hebrew; for they have twenty-two elementary sounds which are pronounced the same way, but are differently written. The Samaritans also write the Pentateuch of Moses with just the same number of letters, differing only in the shape and points of the letters. And it is certain that Esdras, the scribe and teacher of the law, after the capture of Jerusalem and the restoration of the temple by Zerubbabel, invented other letters which we now use, for up to that time the Samaritan and Hebrew characters were the same. In the book of Numbers, moreover, where we have the census of the Levites and priests [Num. 3:39], the same total is presented mystically. And we find the four-lettered name of the Lord [tetragrammaton] in certain Greek books written to this day in the ancient characters. The thirty-seventh Psalm, moreover, the one hundred and eleventh, the one hundred and twelfth, the one hundred and nineteenth, and the one hundred and forty-fifth, although they are written in different metres, are all composed [as acrostics] according to an alphabet of the same number of letters. The Lamentations of Jeremiah, and his Prayer, the Proverbs of Solomon also, towards the end, from the place where we read "Who will find a steadfast woman?" are instances of the same number of letters forming the division into sections. Furthermore, five are double letters, viz., Caph, Mem, Nun, Phe, Sade, for at the beginning and in the middle of words they are written one way, and at the end another way. Whence it happens that, by most people, five of the books are reckoned as double, viz., Samuel, Kings, Chronicles, Ezra, and Jeremiah with Kinoth, i.e., his Lamentations. As, then, there are twenty-two elementary characters by means of which we write in Hebrew all we say, and the human voice is comprehended within their limits, so we reckon twenty-two books, by which, as by the alphabet of the doctrine of God, a righteous man is instructed in tender infancy, and, as it were, while still at the breast. The first of these books is called Bresith, to which we give the name Genesis. The second, Elle Smoth, which bears the name Exodus; the third, Vaiecra, that is Leviticus; the fourth, Vaiedabber, which we call Numbers; the fifth, Elle Addabarim, which is entitled Deuteronomy. These are the five books of Moses, which they properly call Thorath, that is, 'Law.' The second class is composed of the Prophets, and they begin with Jesus the son of Nave, which among them is called Joshua ben Nun. Next in the series is Sophtim, that is the book of Judges; and in the same book they include Ruth, because the events narrated occurred in the days of the Judges. Then comes Samuel, which we call First and Second Kings. The fourth is Malachim, that is, Kings, which is contained in the third and fourth volumes of Kings. And it is far better to say Malachim, that is Kings, than Malachoth, that is Kingdoms. For the author does not describe the Kingdoms of many nations, but that of one people, the people of Israel, which is comprised in the twelve tribes. The fifth is Isaiah; the sixth, Jeremiah; the seventh, Ezekiel; and the eighth is the book of the Twelve Prophets, which is called among them Thare Asra. To the third class belong the Hagiographa, of which the first book begins with Job; the second with David, whose writings they divide into five parts and comprise in one volume of Psalms. The third is Solomon, in three books: Proverbs, which they call Parables, that is Masaloth; Ecclesiastes, that is Coeleth; and the Song of Songs, which they denote by the title Sir Assirim. The sixth is Daniel; the seventh, Dabre Aiamim, that is, Words of Days, which we may more descriptively call a chronicle of the whole of the sacred history, the book that amongst us is called First and Second Paralipomenon [Chronicles]. The eighth is Ezra, which itself is likewise divided amongst Greeks and Latins into two books; the ninth is Esther. And so there are also twenty-two books of the Old Law; that is, five of Moses, eight of the prophets, nine of the Hagiographa, though some include Ruth and Kinoth (Lamentations) amongst the Hagiographa, and think that these books ought to be reckoned separately; we should thus have twenty-four books of the ancient Law. And these the Apocalypse of John represents by the twenty-four elders, who adore the Lamb and offer their crowns with lowered visage, while in their presence stand the four living creatures with eyes before and behind, that is, looking to the past and the future, and with unwearied voice crying, "Holy, Holy, Holy, Lord God Almighty, who was and is and will be." This preface to the Scriptures may serve as a helmeted [i.e. defensive] introduction to all the books which we turn from Hebrew into Latin, so that we may be assured that what is outside of them must be placed aside among the Apocryphal writings. Wisdom, therefore, which generally bears the name of Solomon, and the book of Jesus the Son of Sirach, and Judith, and Tobias, and the Shepherd [of Hermes?] are not in the canon. The first book of Maccabees is found in Hebrew, but the second is Greek, as can be proved from the very style. Although these things are thus, I beseech you, my reader, not to think that my labours are intended to disparage the ancients [i.e. the translators of the older versions]. For the service of the tabernacle of God each one offers what he can; some gold and silver and precious stones, others linen and blue and purple and scarlet; we shall do well if we offer skins and goats' hair [cf. Exod.25:3-5]. And yet the Apostle pronounces our more contemptible things more necessary than others [1 Cor. 12:22]. Accordingly, the beauty of the tabernacle as a whole and in its several kinds (and the ornaments of the church present and future) was covered with skins and goat-hair cloths, and the heat of the sun and the injurious rain were warded off by those things which are of less account. First read, then, my Samuel and Kings; mine, I say, mine. For whatever by diligent translation and by anxious emendation we have learnt and made our own, is ours. And when you understand something of which you were before ignorant, reckon me a translator if you are grateful, or a paraphraser if ungrateful, although I am not in the least conscious of having deviated from the Hebrew original. At all events, if you are incredulous, read the Greek and Latin manuscripts and compare them with these poor efforts of mine, and wherever you see they disagree, ask some Hebrew in whom you can have more faith, and if he confirm our view, I suppose you will not think him a soothsayer and suppose that he and I have, in rendering the same passage, divined alike. But I ask you also, handmaidens of Christ, who anoint the head of your reclining Lord with the most precious myrrh of faith, who by no means seek the Saviour in the tomb, for whom Christ has long since ascended to the Father—I beg you to confront with the shields of your prayers the dogs who bark and rage against me with rabid mouths, and who go about the city, and think themselves learned if they disparage others. Knowing my lowliness, I will always remember what we are told: "I said, I will take heed to my ways that I offend not in my tongue. I have set a guard upon my mouth while the sinner standeth against me. I became dumb, and was humbled, and kept silence from good words." [Psalm 38:2-3]”74 75 76 77

- Jerome of Stridon, Prologue to the Books of the Kings, this English translation is based upon W. H. Fremantle's (with just a couple of changes to make the translation more literal), which appeared in A Select Library of the Nicene and Post-Nicene Fathers of the Christian Church, second series, vol. 6, St. Jerome; Letters and Select Works (Christian Literature Publishing Co., 1893).

“Genesis, we shall be told, needs no explanation; its topics are too simple—the birth of the world, the origin of the human race, the division of the earth, the confusion of tongues, and the descent of the Hebrews into Egypt! Exodus, no doubt, is equally plain, containing as it does merely an account of the ten plagues, the decalogue, and sundry mysterious and divine precepts! The meaning of Leviticus is of course self-evident, although every sacrifice that it describes, nay more every word that it contains, the description of Aaron’s vestments, and all the regulations connected with the Levites are symbols of things heavenly! The book of Numbers too—are not its very figures, and Balaam’s prophecy, and the forty-two camping places in the wilderness so many mysteries? Deuteronomy also, that is the second law or the foreshadowing of the law of the gospel,—does it not, while exhibiting things known before, put old truths in a new light? So far the ‘five words’ of the Pentateuch, with which the apostle boasts his wish to speak in the Church. Then, as for Job, that pattern of patience, what mysteries are there not contained in his discourses? Commencing in prose the book soon glides into verse and at the end once more reverts to prose. By the way in which it lays down propositions, assumes postulates, adduces proofs, and draws inferences, it illustrates all the laws of logic. Single words occurring in the book are full of meaning. To say nothing of other topics, it prophesies the resurrection of men’s bodies at once with more clearness and with more caution than any one has yet shewn. “I know,” Job says, “that my redeemer liveth, and that at the last day I shall rise again from the earth; and I shall be clothed again with my skin, and in my flesh shall I see God. Whom I shall see for myself, and mine eyes shall behold, and not another. This my hope is stored up in my own bosom.” I will pass on to Jesus the son of Nave [i.e. - Joshua]—a type of the Lord in name as well as in deed—who crossed over Jordan, subdued hostile kingdoms, divided the land among the conquering people and who, in every city, village, mountain, river, hill-torrent, and boundary which he dealt with, marked out the spiritual realms of the heavenly Jerusalem, that is, of the church. In the book of Judges every one of the popular leaders is a type. Ruth the Moabitess fulfils the prophecy of Isaiah:—”Send thou a lamb, O Lord, as ruler of the land from the rock of the wilderness to the mount of the daughter of Zion.” Under the figures of Eli’s death and the slaying of Saul Samuel shews the abolition of the old law. Again in Zadok and in David he bears witness to the mysteries of the new priesthood and of the new royalty. The third and fourth books of Kings called in Hebrew Malâchim give the history of the kingdom of Judah from Solomon to Jeconiah, and of that of Israel from Jeroboam the son of Nebat to Hoshea who was carried away into Assyria. If you merely regard the narrative, the words are simple enough, but if you look beneath the surface at the hidden meaning of it, you find a description of the small numbers of the church and of the wars which the heretics wage against it. The twelve prophets whose writings are compressed within the narrow limits of a single volume, have typical meanings far different from their literal ones. Hosea speaks many times of Ephraim, of Samaria, of Joseph, of Jezreel, of a wife of whoredoms and of children of whoredoms, of an adulteress shut up within the chamber of her husband, sitting for a long time in widowhood and in the garb of mourning, awaiting the time when her husband will return to her. Joel the son of Pethuel describes the land of the twelve tribes as spoiled and devastated by the palmerworm, the canker-worm, the locust, and the blight, and predicts that after the overthrow of the former people the Holy Spirit shall be poured out upon God’s servants and handmaids; the same spirit, that is, which was to be poured out in the upper chamber at Zion upon the one hundred and twenty believers. These believers rising by gradual and regular gradations from one to fifteen form the steps to which there is a mystical allusion in the “psalms of degrees.” Amos, although he is only “an herdman” from the country, “a gatherer of sycomore fruit,” cannot be explained in a few words. For who can adequately speak of the three transgressions and the four of Damascus, of Gaza, of Tyre, of Idumæa, of Moab, of the children of Ammon, and in the seventh and eighth place of Judah and of Israel? He speaks to the fat kine that are in the mountain of Samaria, and bears witness that the great house and the little house shall fall. He sees now the maker of the grasshopper, now the Lord, standing upon a wall daubed or made of adamant, now a basket of apples that brings doom to the transgressors, and now a famine upon the earth “not a famine of bread, nor a thirst for water, but of hearing the words of the Lord.” Obadiah, whose name means the servant of God, thunders against Edom red with blood and against the creature born of earth. He smites him with the spear of the spirit because of his continual rivalry with his brother Jacob. Jonah, fairest of doves, whose shipwreck shews in a figure the passion of the Lord, recalls the world to penitence, and while he preaches to Nineveh, announces salvation to all the heathen. Micah the Morasthite a joint heir with Christ announces the spoiling of the daughter of the robber and lays siege against her, because she has smitten the jawbone of the judge of Israel. Nahum, the consoler of the world, rebukes “the bloody city” and when it is overthrown cries:—”Behold upon the mountains the feet of him that bringeth good tidings.” Habakkuk, like a strong and unyielding wrestler, stands upon his watch and sets his foot upon the tower that he may contemplate Christ upon the cross and say “His glory covered the heavens and the earth was full of his praise. And his brightness was as the light; he had horns coming out of his hand: and there was the hiding of his power.” Zephaniah, that is the bodyguard and knower of the secrets of the Lord, hears “a cry from the fishgate, and an howling from the second, and a great crashing from the hills.” He proclaims “howling to the inhabitants of the mortar; for all the people of Canaan are undone; all they that were laden with silver are cut off.” Haggai, that is he who is glad or joyful, who has sown in tears to reap in joy, is occupied with the rebuilding of the temple. He represents the Lord (the Father, that is) as saying “Yet once, it is a little while, and I will shake the heavens, and the earth, and the sea, and the dry land; and I will shake all nations and he who is desired of all nations shall come.” Zechariah, he that is mindful of his Lord, gives us many prophecies. He sees Jesus, “clothed with filthy garments,” a stone with seven eyes, a candle-stick all of gold with lamps as many as the eyes, and two olive trees on the right side of the bowl and on the left. After he has described the horses, red, black, white, and grisled, and the cutting off of the chariot from Ephraim and of the horse from Jerusalem he goes on to prophesy and predict a king who shall be a poor man and who shall sit “upon a colt the foal of an ass.” Malachi, the last of all the prophets, speaks openly of the rejection of Israel and the calling of the nations. “I have no pleasure in you, saith the Lord of hosts, neither will I accept an offering at your hand. For from the rising of the sun even unto the going down of the same, my name is great among the Gentiles: and in every place incense is offered unto my name, and a pure offering.” As for Isaiah, Jeremiah, Ezekiel, and Daniel, who can fully understand or adequately explain them? The first of them seems to compose not a prophecy but a gospel. The second speaks of a rod of an almond tree and of a seething pot with its face toward the north, and of a leopard which has changed its spots. He also goes four times through the alphabet in different metres. The beginning and ending of Ezekiel, the third of the four, are involved in so great obscurity that like the commencement of Genesis they are not studied by the Hebrews until they are thirty years old. Daniel, the fourth and last of the four prophets, having knowledge of the times and being interested in the whole world, in clear language proclaims the stone cut out of the mountain without hands that overthrows all kingdoms. David, who is our Simonides, Pindar, and Alcæus, our Horace, our Catullus, and our Serenus all in one, sings of Christ to his lyre; and on a psaltery with ten strings calls him from the lower world to rise again. Solomon, a lover of peace and of the Lord, corrects morals, teaches nature, unites Christ and the church, and sings a sweet marriage song to celebrate that holy bridal. Esther, a type of the church, frees her people from danger and, after having slain Haman whose name means iniquity, hands down to posterity a memorable day and a great feast. The book of things omitted or epitome of the old dispensation is of such importance and value that without it any one who should claim to himself a knowledge of the scriptures would make himself a laughing stock in his own eyes. Every name used in it, nay even the conjunction of the words, serves to throw light on narratives passed over in the books of Kings and upon questions suggested by the gospel. Ezra and Nehemiah, that is the Lord’s helper and His consoler, are united in a single book. They restore the Temple and build up the walls of the city. In their pages we see the throng of the Israelites returning to their native land, we read of priests and Levites, of Israel proper and of proselytes; and we are even told the several families to which the task of building the walls and towers was assigned. These references convey one meaning upon the surface, but another below it. You see how, carried away by my love of the scriptures, I have exceeded the limits of a letter yet have not fully accomplished my object. We have heard only what it is that we ought to know and to desire, so that we too may be able to say with the psalmist:—”My soul breaketh out for the very fervent desire that it hath alway unto thy judgments.” But the saying of Socrates about himself—”this only I know that I know nothing”—is fulfilled in our case also.

The New Testament I will briefly deal with. Matthew, Mark, Luke and John are the Lord’s team of four, the true cherubim or store of knowledge. With them the whole body is full of eyes, they glitter as sparks, they run and return like lightning, their feet are straight feet, and lifted up, their backs also are winged, ready to fly in all directions. They hold together each by each and are interwoven one with another: like wheels within wheels they roll along and go whithersoever the breath of the Holy Spirit wafts them. The apostle Paul writes to seven churches (for the eighth epistle—that to the Hebrews—is not generally counted in with the others). He instructs Timothy and Titus; he intercedes with Philemon for his runaway slave. Of him I think it better to say nothing than to write inadequately. The Acts of the Apostles seem to relate a mere unvarnished narrative descriptive of the infancy of the newly born church; but when once we realize that their author is Luke the physician whose praise is in the gospel, we shall see that all his words are medicine for the sick soul. The apostles James, Peter, John, and Jude, have published seven epistles at once spiritual and to the point, short and long, short that is in words but lengthy in substance so that there are few indeed who do not find themselves in the dark when they read them. The apocalypse of John has as many mysteries as words. In saying this I have said less than the book deserves. All praise of it is inadequate; manifold meanings lie hid in its every word. I beg of you, my dear brother, to live among these books, to meditate upon them, to know nothing else, to seek nothing else.”78

- Jerome of Stridon, Letter 53 “To Paulinus”, (Ad Paulinum, no. 53 § 8), link: https://www.ccel.org/ccel/schaff/npnf206.v.LIII.html

“Let her treasures be not silks or gems but manuscripts of the holy scriptures; and in these let her think less of gilding, and Babylonian parchment, and arabesque patterns, than of correctness and accurate punctuation. Let her begin by learning the psalter, and then let her gather rules of life out of the proverbs of Solomon. From the Preacher [i.e.- Ecclesiastes] let her gain the habit of despising the world and its vanities. Let her follow the example set in Job of virtue and of patience. Then let her pass on to the gospels never to be laid aside when once they have been taken in hand. Let her also drink in with a willing heart the Acts of the Apostles and the Epistles. As soon as she has enriched the storehouse of her mind with these treasures, let her commit to memory the prophets, the heptateuch, the books of Kings and of Chronicles, the rolls also of Ezra and Esther. When she has done all these she may safely read the Song of Songs but not before: for, were she to read it at the beginning, she would fail to perceive that, though it is written in fleshly words, it is a marriage song of a spiritual bridal. And not understanding this she would suffer hurt from it. Let her avoid all apocryphal writings, and if she is led to read such not by the truth of the doctrines which they contain but out of respect for the miracles contained in them; let her understand that they are not really written by those to whom they are ascribed, that many faulty elements have been introduced into them, and that it requires infinite discretion to look for gold in the midst of dirt. Cyprian’s writings let her have always in her hands. The letters of Athanasius and the treatises of Hilary she may go through without fear of stumbling. Let her take pleasure in the works and wits of all in whose books a due regard for the faith is not neglected. But if she reads the works of others let it be rather to judge them than to follow them.”79

- Jerome of Stridon, Epistle 107 (“To Laeta”), 12, link: https://www.ccel.org/ccel/schaff/npnf206.v.CVII.html

“Among the Hebrews, the book of Judith is read among the Hagiographa; its authority is judged to be less suitable for reinforcing those things that come into contention.”80 81

- Jerome of Stridon, Prologue to Judith, SACRED BIBLE VULGATE, vol. 1, p. 691.

“This prologue of the Scriptures, as a helmeted introduction to all the books that we have translated from Hebrew into Latin, can serve to inform us that anything outside of these should be set aside among the apocrypha. Therefore, the Wisdom which is commonly inscribed as of Solomon, and the book of Jesus son of Sirach, and Judith, and Tobit, and the Shepherd are not in the canon. I found the first book of the Maccabees in Hebrew; the second is Greek, which can be proven from its very nature.”82 83

- Jerome of Stridon, Prologue to the Books of Kings, SACRED BIBLE VULGATE.

“Simon Peter ... wrote two epistles which are called catholic, the second of which, on account of its difference from the first in style, is considered by many not to be by him. Then too the gospel according to Mark, who was his hearer and interpreter, is said to be his. On the other hand, the books of which one is entitled his acts, another his gospel, a third his preaching, a fourth his revelation, a fifth his judgment, are repudiated as apocryphal.”84

- Jerome, On Famous Men, Chapter 1.

“This must be said to our people, that the epistle which is entitled "To the Hebrews" is accepted as the apostle Paul's not only by the churches of the east but by all church writers in the Greek language of earlier times, although many judge it to be by Barnabas or by Clement. It is of no great moment who the author is, since it is the work of a churchman and receives recognition day by day in the public reading of the churches. If the custom of the Latins does not receive it among the canonical scriptures, neither, by the same liberty, do the churches of the Greeks accept John's Apocalypse. Yet we accept them both, not following the custom of the present time but the precedent of early writers, who generally make free use of testimonies from both works. And this they do, not as they are wont on occasion to quote from apocryphal writings, as indeed they use examples from pagan literature, but treating them as canonical and churchly works.”85 86

- Jerome, Letter to Dardanus, prefect of Gaul (Ad Dardanum, no. 129 § 3).

“Both sinners and just are saved by the Lord’s propitiation - as the apostle Paul says: ‘We are reconciled to God by the blood of his Son’ (Rom 5:10); and it is said concerning sinners that they have the measure of half a cubit round about, who nevertheless may be saved by the Creator's mercy. This agrees with what is written in the Psalm: ‘You shall save them for nothing’ (Ps 56:7). Concerning the just — they are saved in one group, solitary and perfect, in imitation of the one divinity . For the Apostle says, ‘God was in Christ reconciling the world to himself’ (2 Cor 5:19). Now as for what is recorded at the end of this citation, and its steps turned toward the east, we ought to understand the steps of this propitiatory either of the twenty-four books of Old Instrument, who had harps in the Apocalypse of John and crowns on their heads (cf. Rev 5:8); or of the mystery of the Father, the Son, and the Holy Spirit, in whom true propitiation is given to us.”87 88

- Jerome of Stridon, “Commentary on Ezekiel” (410-414) 13.43:13-17, CCSL 75:635, in: Jerome, “Commentary on Ezekiel,” trans. Thomas P. Scheck, Newman Press, New York 2017, p. 508.

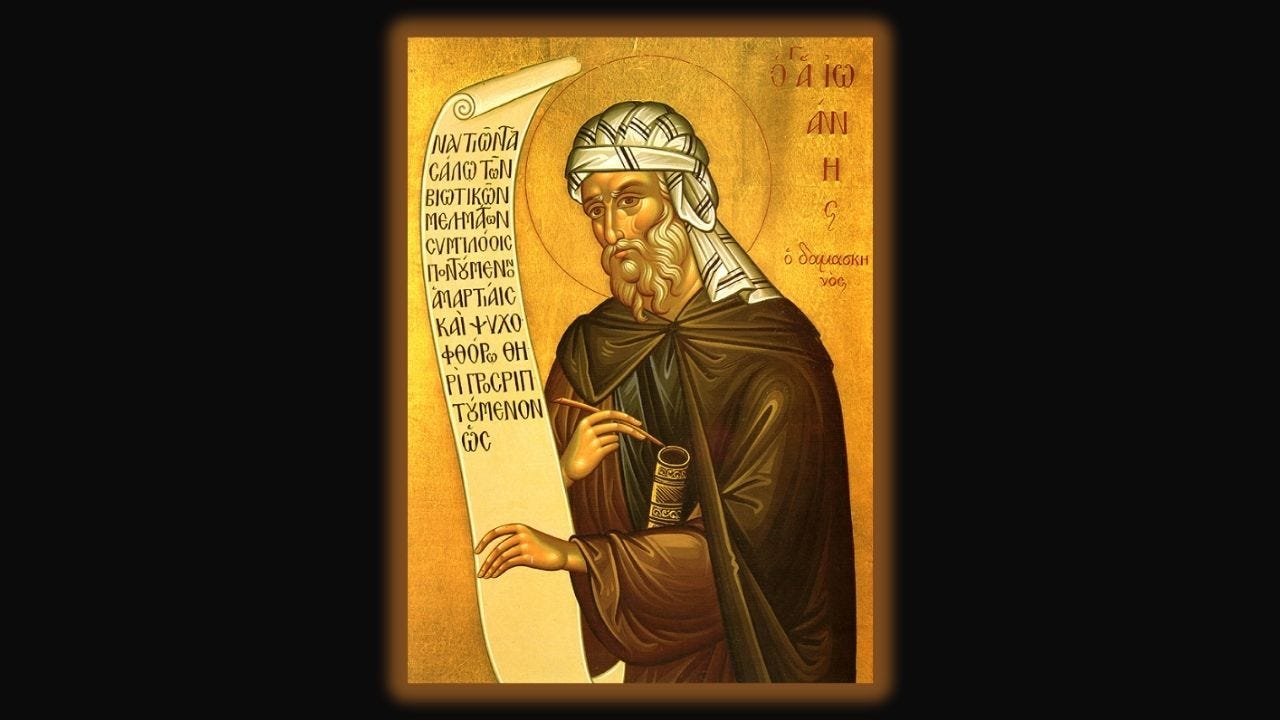

JOHN OF DAMASCUS (c. 675-749 AD)

Historical/Biographical Details: 89

“Observe, further, that there are two and twenty books of the Old Testament, one for each letter of the Hebrew tongue. For there are twenty-two letters of which five are double, and so they come to be twenty-seven. For the letters Caph, Mem, Nun, Pe, Sade are double. And thus the number of the books in this way is twenty-two, but is found to be twenty-seven because of the double character of five. For Ruth is joined on to Judges, and the Hebrews count them one book: the first and second books of Kings are counted one: and so are the third and fourth books of Kings: and also the first and second of Paraleipomena: and the first and second of Esdra. In this way, then, the books are collected together in four Pentateuchs and two others remain over, to form thus the canonical books. Five of them are of the Law, viz. Genesis, Exodus, Leviticus, Numbers, Deuteronomy. This which is the code of the Law, constitutes the first Pentateuch. Then comes another Pentateuch, the so-called Grapheia, or as they are called by some, the Hagiographa, which are the following: Jesus the Son of Nave, Judges along with Ruth, first and second Kings, which are one book, third and fourth Kings, which are one book, and the two books of the Paraleipomena which are one book. This is the second Pentateuch. The third Pentateuch is the books in verse, viz. Job, Psalms, Proverbs of Solomon, Ecclesiastes of Solomon and the Song of Songs of Solomon. The fourth Pentateuch is the Prophetical books, viz the twelve prophets constituting one book, Isaiah, Jeremiah, Ezekiel, Daniel. Then come the two books of Esdra made into one, and Esther. There are also the Panaretus, that is the Wisdom of Solomon, and the Wisdom of Jesus, which was published in Hebrew by the father of Sirach, and afterwards translated into Greek by his grandson, Jesus, the Son of Sirach. These are virtuous and noble, but are not counted nor were they placed in the ark. The New Testament contains four gospels, that according to Matthew, that according to Mark, that according to Luke, that according to John: the Acts of the Holy Apostles by Luke the Evangelist: seven catholic epistles, viz. one of James, two of Peter, three of John, one of Jude: fourteen letters of the Apostle Paul: the Revelation of John the Evangelist: the Canons of the holy apostles, by Clement.”90

- John of Damascus, NPNF2-09, An Exact Exposition of the Orthodox Faith, Book IV, Chapter XVII, link: https://www.ccel.org/ccel/schaff/npnf209.iii.iv.iv.xvii.html

JOSEPPUS – A.K.A: JOSEPH THE CHRISTIAN (10th CENTURY AD)

Historical/Biographical Details: 91

“The twenty-two books included in the Old Testament: 1. Bereshith, that is, in the beginning he created [i.e. - Genesis]. 2. Shemot, that is, here are the names [i.e. - Exodus]. 3. Vayikra, that is, and he called [i.e. - Leviticus]. 4. Bamidbar, Numbers. 5. Devarim, Deuteronomy, these are the words. 6. Joshua, son of Nun. 7. Judges. 8. Ruth. 9. Samuel, which translates to "called." 10. And King David, that is, King David. 11. The words of the days. 12. Ezra, the scribe, book. 13. Tehillim, that is, the book of Psalms. 14. Proverbs. 15. Ecclesiastes. 16. Song of Songs. 17. Twelve Prophets. 18. Isaiah. 19. Jeremiah. 20. Ezekiel. 21. Daniel. 22. Job. Besides these, Esther and the books of the Maccabees, titled Sarbeth Sabanaiel.”92 93

- Jossepus, Hypomnestikon, cited in Joseph the Christian’s Bible notes: Hypomnestikon, 1996, pages 86-87.

JUNILIUS AFRICANUS (6th CENTURY AD)

Historical/Biographical Details: 94

“They [i.e. - Chronicles, Job, Ezra, Judith, Esther, Maccabees] are not included among the Canonical Scriptures, because they were received among the Hebrews only in a secondary rank, as Jerome and others testify.”95 96

- Junilius Africanus, cited by B. F. Westcott, The Bible in the Church: A Popular Account Of the Collection And Reception Of The Holy Scriptures In The Christian Churches, 1879, Macmillan & Co.: London, Pg. 194, link: https://archive.org/details/thebibleinthechu00westuoft/page/n221/mode/1up

LEONTIUS OF JERUSALEM - a.k.a: LEONTIUS BYZANTINUS (c. 485-543 AD)

Historical/Biographical Details: 97

“Of the Old Testament there are twenty-two books... The historical books are twelve... The first five, called the Pentateuch, are according to universal testimony the books of Moses: those which follow are of unknown authors, namely Joshua... Judges... Ruth... Kings (in two books)... Chronicles... Ezra... The prophetic books are five, Isaiah, Jeremiah, Ezekiel, Daniel, the twelve prophets... The didactic books are four, Job, which some thought to be a composition of Josephus, Proverbs, Ecclesiastes, Canticles… These three books are Solomon’s. The Psalter follows. [In these] you have the books of the Old Scripture. Of the New there are six books. Of these two contain the four Evangelists, the first Matthew and Mark, the second, Luke and John. The third is the Acts of the Apostles. The fourth the Catholic Epistles, in number seven...They are called catholic or general, because they are not written to one nation, as those of St Paul, but generally to all. The fifth is the fourteen Epistles of St Paul. The sixth, the Apocalypse of St John. These are the books reckoned as canonical in the Church, both old and new; of which the Hebrews receive all the old.”98 99

- Leontius of Jerusalem, cited by B. F. Westcott, A General Survey Of the History Of the Canon Of the New Testament, 1896, Seventh Edition, Macmillan & Co. Ltd. London, p. 568.

MELITO OF SARDIS (c. 100-180 AD)

Historical/Biographical Details: 100

“I accordingly proceeded to the East, and went to the very spot where the things in question were preached and took place; and, having made myself accurately acquainted with the books of the Old Testament, I have set them down below, and herewith send you the list. Their names are as follows:— The five books of Moses—Genesis, Exodus, Leviticus, Numbers, Deuteronomy; Joshua, Judges, Ruth, the four books of Kings, the two of Chronicles, the book of the Psalms of David, the Proverbs of Solomon, also called the Book of Wisdom, Ecclesiastes, the Song of Songs, Job, the books of the prophets Isaiah, Jeremiah, of the twelve contained in a single book, Daniel, Ezekiel, Esdras. From these I have made my extracts, dividing them into six books.”101

- Melito of Sardis, ANF08, Book of Extracts, Fragment IV, link: https://www.ccel.org/ccel/schaff/anf08.x.v.xi.html#fnf_x.v.xi-p7.1102

ORIGEN OF ALEXANDRIA (185- c. 253 AD)

Historical/Biographical Details: 103 104

“When expounding the first Psalm, he [Origen] gives a catalogue of the sacred Scriptures of the Old Testament as follows: “It should be stated that the canonical books, as the Hebrews have handed them down, are twenty-two; corresponding with the number of their letters.” Farther on he says: “The twenty-two books of the Hebrews are the following: That which is called by us Genesis, but by the Hebrews, from the beginning of the book, Bresith, which means, ‘In the beginning’; Exodus, Welesmoth, that is, ‘These are the names’; Leviticus, Wikra, ‘And he called‘; Numbers, Ammesphekodeim; Deuteronomy, Eleaddebareim, ‘These are the words’; Jesus, the son of Nave, Josoue ben Noun; Judges and Ruth, among them in one book, Saphateim; the First and Second of Kings, among them one, Samouel, that is, ‘The called of God’; the Third and Fourth of Kings in one, Wammelch David, that is, ‘The kingdom of David’; of the Chronicles, the First and Second in one, Dabreïamein, that is, ‘Records of days’; Esdras, First and Second in one, Ezra, that is, ‘An assistant’; the book of Psalms, Spharthelleim; the Proverbs of Solomon, Meloth; Ecclesiastes, Koelth; the Song of Songs (not, as some suppose, Songs of Songs), Sir Hassirim; Isaiah, Jessia; Jeremiah, with Lamentations and the epistle in one, Jeremia; Daniel, Daniel; Ezekiel, Jezekiel; Job, Job; Esther, Esther. And besides these there are the Maccabees, which are entitled Sarbeth Sabanaiel.””105 106 107 108

- Eusebius citing Origen, NPNF2-01, The Church History of Eusebius, Chapter XXV.—His Review of the Canonical Scriptures, link: https://www.ccel.org/ccel/schaff/npnf201.iii.xi.xxv.html#fna_iii.xi.xxv-p2.2

PRIMASIUS OF HADRUMETUM (1096-1141 AD)

Historical/Biographical Details: 109 110